Using New Materials to Treat an Old Problem

Using New Materials to Treat an Old Problem

A shared lab leads to a game-changing solution.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of people in the United States break a rib, making rib fractures one of the most common traumatic injuries.

Yet, except for the most extreme cases, there is no treatment beyond rest and pain control.

There are a lot of problems with that scenario, according to Joseph Fernandez-Moure, M.D., assistant professor of surgery. He's a trauma surgeon and works with a lot of patients who have broken ribs.

Unlike a broken leg, a broken rib can't be immobilized with a cast because that would interfere with breathing. But without immobilization, breathing hurts and coughing can be excruciating. “When broken bones start rubbing up against each other, the pain can be debilitating,” Fernandez-Moure says.

Rib fracture patients also are at risk for developing pneumonia due to the combination of shallow breathing and a build-up of fluids from the injury, so they are prescribed deep breathing exercises called “pulmonary hygiene.” But pain makes it hard to comply, especially among older patients, who make up a growing percentage of rib-fracture cases as the population ages. Pain can be controlled with opioids, but they carry the risk of addiction.

“Imagine being a laborer of any sort, having a job that requires you to do lifting or turning. Putting food on the table becomes a real problem.”

Joe Fernandez-Moure

Even for those who escape infection or addiction, it can be an emotional or financial blow to be forced to drastically restrict movement for the six to eight weeks it takes to heal.

“Quality of life is significantly impacted when you can't fix these people,” he says. “Imagine being a laborer of any sort, having a job that requires you to do lifting or turning. Putting food on the table becomes a real problem.”

As a surgeon-scientist, Fernandez-Moure likes to fix problems for his patients, and he likes to do that using multidisciplinary collaborations with other physicians and scientists. So when he joined the Duke faculty in the fall of 2019, he was on the lookout for a materials science researcher to work with. He figured a better way to treat rib fractures was going to involve new materials, not metal plates and pins.

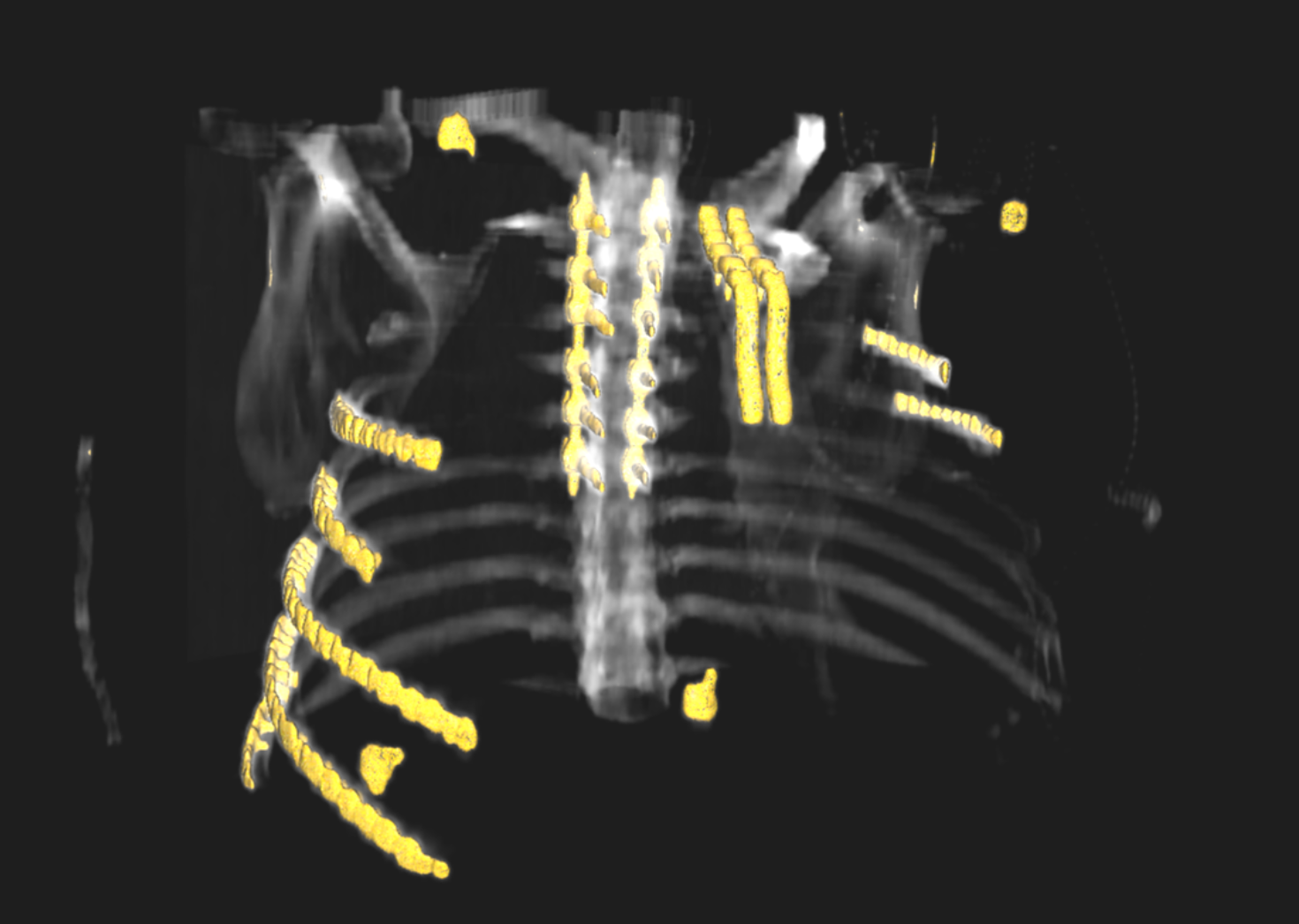

Severe chest wall injury in a 3D reconstruction of a patient CT scan.

Photo credit Joe Fernandez-Moure

As luck would have it, his future collaborator, Matthew Becker, Ph.D., arrived at Duke the same month, and the two bumped into each other at a new employee orientation meeting. Becker is the Hugo L. Blomquist Distinguished Professor of Chemistry, with multiple appointments in mechanical engineering and materials science, biomedical engineering and orthopaedic surgery.

The two had met almost a decade earlier when they both worked on the same large federally funded project, though they were at different institutions. However, they'd lost touch over the years.

“I didn't even know he was going to be at Duke,” Becker says. “We had a beer after orientation and pretty soon decided that he would embed himself and his team in my research lab.”

Becker creates new materials, including degradable polymers for medical applications. Like Fernandez-Moure, he is motivated to fix real-world problems, but he also keeps one foot firmly planted in basic science.

“The underpinning of basic research is the deep knowledge that allows you to respond rapidly to challenges,” Becker says. “Without that continuous effort of trying to understand why, as opposed to trying to understand how, you don't go very far.”

Fernandez-Moure knew that Becker's lab had developed an adhesive that could be slowly absorbed by the body. He wondered if it could be injected into broken ribs. “The idea would be to stabilize the rib as it was before the injury to allow you to continue your rehab and your breathing,” he says.

One of the first steps, beginning this month, is to start preclinical trials and performing mechanical tests in the lab — simulating the breaking of a rib and then injecting it with the polymer adhesive. If successful, the two would begin clinical trials to evolve it into a widely available therapy.

“The underpinning of basic research is the deep knowledge that allows you to respond rapidly to challenges. Without that continuous effort of trying to understand why, as opposed to trying to understand how, you don't go very far.”

Matt Becker

The two expect to work on more projects together in the future. Sharing physical lab space practically guarantees it. “I try to get to as many of their lab meetings as I possibly can,” Fernandez-Moure says. “I love it because it gives me an inside look into what they are doing. Every time I hear about a new project, something in my mind pops up immediately that it could be a solution for.”

Fernandez-Moure was drawn to working with Becker for another reason besides their complementary professional expertise. “If you look at Matt's lab, there are people of all ethnicities, color, genders, and races, and that's important to me being a Hispanic in surgery,” he says. “I have been very focused on trying to be a proponent of academic and cultural diversity.”

Becker and Fernandez-Moure fit right in with Duke's culture of team science, and in fact both chose Duke because of it. “The hospital and the university function as one in my mind,” says Fernandez-Moure. “There are distinctions, but merely on paper. The collaborative environment here is the best I've ever seen.”

The School of Medicine is part of what drew Becker, who wanted to be at an institution with a flagship medical school because of his interest in solving medical problems.

“Many institutions say they do multidisciplinary work and there's evidence of it,” Becker says, “But at Duke, multidisciplinary work really bleeds across everything, from curriculum to programming to resource sharing, to create a pretty seamless ecosystem for working together.”

He adds, “The other thrilling thing about Duke is the amount of talent at every level, from faculty to staff to students.”

The future of Duke Science and Technology begins with you

Duke Science and Technology is one of Duke’s biggest priorities. Your investment in our researchers, our students and our work will have exponential impact on society and our world.